Siena: The Palazzo Publico

In the last post, we took a look at Duccio’s Maesta (1308-1311), his enormous altarpiece of many panels that, in its original form, was an elaborately framed, two-sided work–perhaps the most glorious single artwork of the late medieval period. It honored the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven . . .

. . . and was located inside Siena Cathedral. Thanks to political links between the City State of Siena and France, the Maesta and the cathedral show a strong French Gothic inflection. The altarpiece with its pinnacles and upward thrusting momentum has a lot in common with the French Gothic facade of the cathedral in which it was located:

Over the years, the frame was removed and lost and the altarpiece itself dismembered, with some panels making their way into distant collections. Most of the parts remain in Siena, though, and as noted earlier we’ll be taking a look at them (now in the cathedral’s museum) on the first part of our visit to this elegant and opulent Tuscan city.

Over the years, the frame was removed and lost and the altarpiece itself dismembered, with some panels making their way into distant collections. Most of the parts remain in Siena, though, and as noted earlier we’ll be taking a look at them (now in the cathedral’s museum) on the first part of our visit to this elegant and opulent Tuscan city.

Later that day, we’ll visit the city hall, the Palazzo Publico, erected in the late 1200s as the governmental headquarters the city. Here’s a general view of this imposing edifice,

which provides the backdrop for the Piazza del Campo, site of the festival Palio della Contrade, which features the racing of the horses each August. Might worth a return trip. Looks dangerous, though.

The piazza will likely be a little calmer the day we gather there to get ready to enter the Palazzo Publico to see works by the Sienese artists Simone Martini and Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

In the council chambers where the city leaders met to deliberate are two famous frescoes by Simone Martini. At one end of the council chamber, filling the entire wall, is Martini’s version of the Maesta, the subject that Duccio had originated. Here’s how Martini treated the subject of Mary as a royal figure presenting the princeling Jesus:

So–two Maestas, one by Duccio and one by Martini. Martini had been Duccio’s student and follows his master’s lead by painting the subject with slender, elongated figures and strong French Gothic overtones (Martini’s virgin wears a robe decorated with the fleur-de-lis). But Duccio painted an altarpiece made up of panel paintings, while Martini painted a fresco filling an enormous wall. Duccio painted for the cathedral, while Martini painted his Maesta for a secular setting, the site of governmental deliberation. Martini’s Mary oversees the deliberations of the council, urging the members toward righteous decisions.

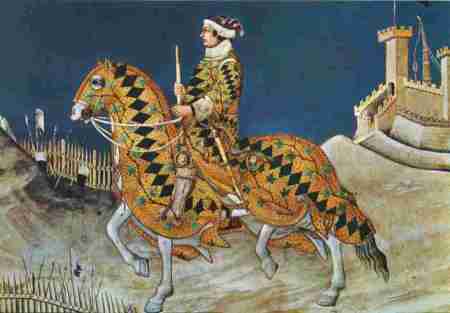

At the other end of the council chamber is another big fresco, traditionally attributed to Martini (some current scholarship questions the attribution, but let’s go with the traditional assumption that the painter was Martini):

This is Martini’s fresco depicting the military man Guidoriccio da Fogliagno, hired by Siena to lead troops to protect the city and bring neighboring villages under Siense influence. Here’s another view of Guidoriccio and his horse, who wear matching outfits:

Consider the irony, or perhaps the common sense, of the placement of Simone’s two frescoes. Mary, enthroned as queen of heaven and implicitly queen of Siena, sits in majesty at one end of the room, while at the other end the soldier Guidoriccio patrols the perimeter of the city. I guess this is a case of covering all bases, of taking out different types of insurance (spiritual, military) just to be sure of comprehensive coverage.

In an adjacent room, the Sala della Pace (Hall of Peace), we’ll see a remarkable set of frescoes by another Sienese master, Ambrogio Lorenzetti. His paintings fill the upper walls of the room and deal with the Effects of Good and Bad Government (always timely subjects). Here’s a general view of the Sala della Pace, showing on the right Lorenzetti’s masterpiece, The Effects of Good Government in the City and Country:

That’s the Siena city wall dividing the composition in two. Within the city, bustling prosperity prevails:

Up among the rooftops just to the right of center, laborers work a construction site. In the foreground, shops do a brisk business and prosperous citizens stroll to and fro. The city, under good government, is so pleasant a place that young women dance in the street:

Up among the rooftops just to the right of center, laborers work a construction site. In the foreground, shops do a brisk business and prosperous citizens stroll to and fro. The city, under good government, is so pleasant a place that young women dance in the street:

Reminds us of the woman celebrating more recently in the streets of Cortona:

Reminds us of the woman celebrating more recently in the streets of Cortona:

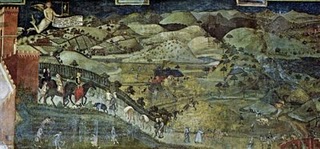

Meanwhile, in the Siena countryside, conditions are flourishing, as well:

Aristocrats head out for a day in the country, while peasants come to town with their produce and products. Vineyards are bountiful, villas dot the land. Lorenzetti’s Effects of Good Government projects an ideal, to be sure: this is civic propaganda of a sort, but the vision is of community we all hope for–prosperous, safe, beautiful in its built and natural environments. Lorenzetti completed this painting in 1339. The hope for such an idyllic place was dashed by the onset of the Black Death, the Great Plague of 1348.

Aristocrats head out for a day in the country, while peasants come to town with their produce and products. Vineyards are bountiful, villas dot the land. Lorenzetti’s Effects of Good Government projects an ideal, to be sure: this is civic propaganda of a sort, but the vision is of community we all hope for–prosperous, safe, beautiful in its built and natural environments. Lorenzetti completed this painting in 1339. The hope for such an idyllic place was dashed by the onset of the Black Death, the Great Plague of 1348.

On the other side of the room, behind us from this view, is Lorenzetti’s depiction of the Effects of Bad Government:

Goodness. The buildings are dilapidated, a corpse lies in the street. Ironically, the work itself is in a state of disrepair. Those splotches are where the plaster has fallen off over the generations. Clearly, it’s in the city of happily dancing girls, the city of prosperity and good government, that we want to be:

Goodness. The buildings are dilapidated, a corpse lies in the street. Ironically, the work itself is in a state of disrepair. Those splotches are where the plaster has fallen off over the generations. Clearly, it’s in the city of happily dancing girls, the city of prosperity and good government, that we want to be:

Look at these great gowns. One features a very nifty dragonfly design. To this day, Italy is a place of fashionable dress, exemplified by Gabriella, our guide in Siena in 2008:

Look at these great gowns. One features a very nifty dragonfly design. To this day, Italy is a place of fashionable dress, exemplified by Gabriella, our guide in Siena in 2008:

A final word: The Sienese artists of the early 14th century were leaders in making art relevant to secular life: daily life in the city and country, government, politics. Martini’s image of Guidoriccio da Fogliano and Lorenzetti’s of Siena and its environs address life beyond the church, life in the civic and communal realm. The Sienese artists of this era began to create art about modern life.

That’s all for now. Ciao!

RH

June 6, 2011 at 5:35 pm

[…] anche il libro che Mallory e Moran hanno dedicato al caso del Guidoriccio) e l’altro blog Siena: The Palazzo Publico che documenta una piacevole visita guidata al monumento gotico. Etichette: affresco, […]

December 5, 2011 at 7:35 pm

Nice photos. Seeing pictures that show a work of art in its original context are very helpful to understanding it at multiple levels. I’m an artist working in proto-Renaissance style and media and I find both Lorenzettis to be a rich source of inspiration.